Alexandru Averescu on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

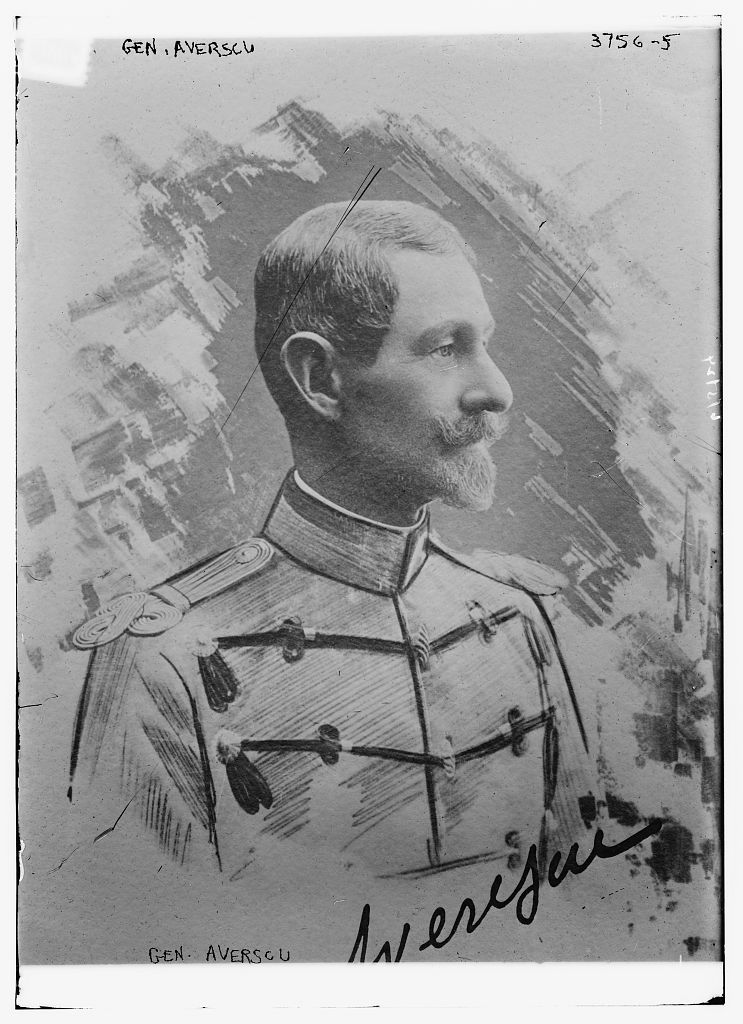

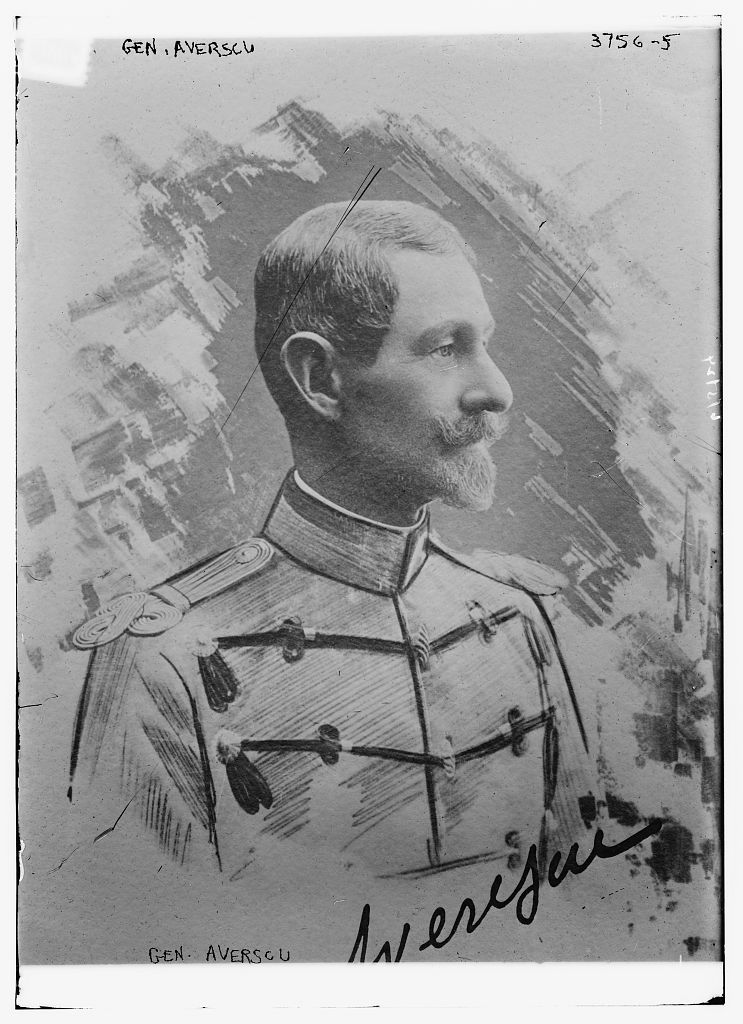

Alexandru Averescu (; 9 March 1859 – 2 October 1938) was a

''Mareșalul Averescu, conducător militar de excepție'' ("Marshal Averescu, Outstanding Military Leader")

at the Sibiu Land Forces Academy; retrieved October 16, 2007 In 1876, he decided to join the

"Suntem cu toții cuprinși de grija cea mare" ("We Are All Overwhelmed by the Greatest of Concerns")

, in ''Magazin Istoric'', October 1997; retrieved October 16, 2007 Averescu married an Italian

''Averescu - 1918''

at th

''Memoria'' Virtual Library

retrieved October 16, 2007 Subsequently, he was commander of the First Infantry Division (stationed in

Averescu again led the Second Army to victory in the

Averescu again led the Second Army to victory in the  During the period, he also faced a Russian Bolshevik military action: just before Averescu came to power, as Russia's

During the period, he also faced a Russian Bolshevik military action: just before Averescu came to power, as Russia's

"Cristian Racovski" (Part I)

, in ''Magazin Istoric'', April 2004; retrieved October 16, 2007 In order to prevent further losses, Averescu signed his name to a much-criticized temporary armistice with the ''Rumcherod''; eventually, Rakovsky was himself faced with a German offensive (sparked by the temporary breakdown of negotiations at Brest-Litovsk), and had to abandon both his command and the base in Odessa.

"Prăbuşirea unui mit" ("A Myth's Crumbling")

, in ''Magazin Istoric'', March 2000; retrieved October 16, 2007 These moves caused a vocal response from the opposition:

"La «kilometrul 0» al comunismului românesc. «S-a terminat definitiv cu comunismul in România!»" ("At «Kilometer 0» in Romanian Communism. «Communism in Romania Is Definitely Over!»")

, in ''

''Bessarabia. Russia and Roumania on the Black Sea'': Chapter XXVIII, "The Tatar-Bunar Episode"

at the

The People's Party involved itself in solving the dynastic crisis after Ferdinand's death in July 1927, again approaching Carol to replace the child-king

The People's Party involved itself in solving the dynastic crisis after Ferdinand's death in July 1927, again approaching Carol to replace the child-king

He ultimately showed himself hostile to Carol's inner circle, and especially to the king's lover

He ultimately showed himself hostile to Carol's inner circle, and especially to the king's lover

''Partidul Național Liberal (Gheorghe Brătianu)'' (summary)

Cap. V, at the

FirstWorldWar.com Biography

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Averescu, Alexandru 1859 births 1938 deaths People from Odesa Oblast People from Bessarabia Governorate Members of the Romanian Orthodox Church Eastern Orthodox Christians from Romania People's Party (interwar Romania) politicians Prime Ministers of Romania Romanian Ministers of Defence Romanian Ministers of Finance Romanian Ministers of Foreign Affairs Romanian Ministers of Industry and Commerce Romanian Ministers of Interior Members of the Senate of Romania Field marshals of Romania Chiefs of the General Staff of Romania Romanian diplomats Romanian military attachés Leaders of political parties in Romania Romanian Gendarmerie personnel Romanian essayists Romanian memoirists Romanian anti-communists Honorary members of the Romanian Academy Romanian military personnel of the Second Balkan War Romanian Army World War I generals Recipients of the Order of Michael the Brave

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

n marshal, diplomat and populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develop ...

politician. A Romanian Armed Forces

The Land Forces, Air Force and Naval Forces of Romania are collectively known as the Romanian Armed Forces ( ro, Forțele Armate Române or ''Armata Română''). The current Commander-in-chief is Lieutenant General Daniel Petrescu who is manage ...

Commander during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, he served as Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

of three separate cabinets (as well as being ''interim'' Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

in January–March 1918 and Minister without portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister who does not head a particular ministry. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet ...

in 1938). He first rose to prominence during the peasants' revolt of 1907, which he helped repress with violence. Credited with engineering the defense of Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

in the 1916–1917 Campaign, he built on his popularity to found and lead the successful People's Party, which he brought to power in 1920–1921, with backing from King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

Ferdinand I and the National Liberal Party (PNL), and with the notable participation of Constantin Argetoianu

Constantin Argetoianu ( – 6 February 1955) was a Romanian politician, one of the best-known personalities of interwar Greater Romania, who served as the Prime Minister between 28 September and 23 November 1939. His memoirs, ''Memorii. Pentr ...

and Take Ionescu.

His controversial first mandate, marked by a political crisis and oscillating support from the PNL's leader Ion I. C. Brătianu

Ion Ionel Constantin Brătianu (, also known as Ionel Brătianu; 20 August 1864 – 24 November 1927) was a Romanian politician, leader of the National Liberal Party (PNL), Prime Minister of Romania for five terms, and Foreign Minister on se ...

, played a part in legislating land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultura ...

and repressed communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

activities, before being brought down by the rally of opposition forces. His second term of 1926–1927 brought a much-debated treaty with Fascist Italy, and fell after Averescu gave clandestine backing to the ousted Prince Carol. Faced with the People Party's decline, Averescu closed deals with various right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that view certain social orders and Social stratification, hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this pos ...

forces and was instrumental in bringing Carol back to the throne in 1930. Relations between the two soured over the following years, and Averescu clashed with his fellow party member Octavian Goga

Octavian Goga (; 1 April 1881 – 7 May 1938) was a Romanian politician, poet, playwright, journalist, and translator.

Life and politics

Goga was born in Rășinari, near Sibiu.

Goga was an active member in the Romanian nationalisti ...

over the king's attitudes. Shortly before his death, he and Carol reconciled, and Averescu joined the Crown Council.

Averescu, who authored over 12 works on various military topics (including his memoirs from the frontline),Petre Otu, "Mareșalul Alexandru Averescu (1859–1938)" ("Marshal Alexandru Averescu"), in ''Dosarele Istoriei'', 2(30)/1999, p.22-23 was also an honorary member of the Romanian Academy and an Order of Michael the Brave

The Order of Michael the Brave ( ro, Ordinul Mihai Viteazul) is Romania's highest military decoration, instituted by King Ferdinand I during the early stages of the Romanian Campaign of the First World War, and was again awarded in the Second Wor ...

recipient. He became a Marshal of Romania in 1930.

Early life and career

Averescu was born in Babele, United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (later renamed to ''Alexandru Averescu'', today Ozerne, a village northwest ofIzmail

Izmail (, , translit. ''Izmail,'' formerly Тучков ("Tuchkov"); ro, Ismail or ''Smil''; pl, Izmaił, bg, Исмаил) is a city and municipality on the Danube river in Odesa Oblast in south-western Ukraine. It serves as the administra ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

). The son of Constantin Averescu, who held the rank

Rank is the relative position, value, worth, complexity, power, importance, authority, level, etc. of a person or object within a ranking, such as:

Level or position in a hierarchical organization

* Academic rank

* Diplomatic rank

* Hierarchy

* ...

of '' sluger'', he studied at the Romanian Orthodox

The Romanian Orthodox Church (ROC; ro, Biserica Ortodoxă Română, ), or Patriarchate of Romania, is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church in full communion with other Eastern Orthodox Christian churches, and one of the nine patriarchates ...

seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy ...

in Izmail, then at the School of Arts and Crafts in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

(intending to become an engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who Invention, invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considerin ...

). Ioan Parean''Mareșalul Averescu, conducător militar de excepție'' ("Marshal Averescu, Outstanding Military Leader")

at the Sibiu Land Forces Academy; retrieved October 16, 2007 In 1876, he decided to join the

Gendarmes

Wrong info! -->

A gendarmerie () is a military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to "men-at-arms" (literally, " ...

in Izmail.

Seeing action as a cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

sergeant with the Romanian troops engaged in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, he was decorated on several occasions, but was later moved to reserve (after failing his medical examination due to the effects of frostbite

Frostbite is a skin injury that occurs when exposed to extreme low temperatures, causing the freezing of the skin or other tissues, commonly affecting the fingers, toes, nose, ears, cheeks and chin areas. Most often, frostbite occurs in t ...

). He was, however, reinstated later in 1878, and subsequently received a military education in Romania, at the military school of Târgoviște

Târgoviște (, alternatively spelled ''Tîrgoviște''; german: Tergowisch) is a city and county seat in Dâmbovița County, Romania. It is situated north-west of Bucharest, on the right bank of the Ialomița River.

Târgoviște was one of ...

( Dealu Monastery), and in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, at the Military Academy of Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

.Constantin Argetoianu

Constantin Argetoianu ( – 6 February 1955) was a Romanian politician, one of the best-known personalities of interwar Greater Romania, who served as the Prime Minister between 28 September and 23 November 1939. His memoirs, ''Memorii. Pentr ...

, "Memorii" ("Memoirs"; fragment), in ''Magazin Istoric'', March 1968, p.71-76, 79-81 Ion Bulei"Suntem cu toții cuprinși de grija cea mare" ("We Are All Overwhelmed by the Greatest of Concerns")

, in ''Magazin Istoric'', October 1997; retrieved October 16, 2007 Averescu married an Italian

opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a libr ...

singer, Clotilda Caligaris, who had been the prima donna

In opera or commedia dell'arte, a prima donna (; Italian for "first lady"; plural: ''prime donne'') is the leading female singer in the company, the person to whom the prime roles would be given.

''Prime donne'' often had grand off-stage per ...

of La Scala

La Scala (, , ; abbreviation in Italian of the official name ) is a famous opera house in Milan, Italy. The theatre was inaugurated on 3 August 1778 and was originally known as the ' (New Royal-Ducal Theatre alla Scala). The premiere performan ...

. His future collaborator and rival Constantin Argetoianu

Constantin Argetoianu ( – 6 February 1955) was a Romanian politician, one of the best-known personalities of interwar Greater Romania, who served as the Prime Minister between 28 September and 23 November 1939. His memoirs, ''Memorii. Pentr ...

stated that Averescu "chose Mrs. Clotilda at random".

Upon his return, Averescu steadily climbed through the ranks. He was head of the Bucharest Military Academy (1894–1895), and, in 1895–1898, Romania's military ''attaché

In diplomacy, an attaché is a person who is assigned ("to be attached") to the diplomatic or administrative staff of a higher placed person or another service or agency. Although a loanword from French, in English the word is not modified accord ...

'' in the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

; a colonel in 1901, he was advanced to the rank of brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

and became head of the Tecuci

Tecuci () is a municipiu, city in Galați County, Romania, in the historical region of Western Moldavia. It is situated among wooded hills, on the right bank of the Bârlad River, and at the junction of railways from Galați, Bârlad, and Mără ...

regional Army Command Center in 1906.

Before the World War, he led the troops in crushing the 1907 peasants' revolt — where he engaged in using very harsh means of repression, especially when dealing with soldiers who refused to fight against the rebels — and was subsequently Minister of War in Dimitrie Sturdza

Dimitrie Sturdza (, in full Dimitrie Alexandru Sturdza-Miclăușanu; 10 March 183321 October 1914) was a Romanian statesman and author of the late 19th century, and president of the Romanian Academy between 1882 and 1884.

Biography

Born in Iași ...

's National Liberal Party (PNL) cabinet (1907–1909).Keith Hitchins

Keith Arnold Hitchins (April 2, 1931 – November 1, 2020) was an American historian and a professor of Eastern European history at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, specializing in Romania and its history.

He was born in Schenect ...

, ''România, 1866–1947'', Humanitas, Bucharest, 1998 (translation of the English-language edition ''Rumania, 1866–1947'', Oxford University Press, USA, 1994), p.184-185, 270, 290-291, 389, 392, 402-403, 406-407 According to the recollections of Eliza Brătianu, a split occurred between him and the PNL after Averescu attempted to advance various political goals — the conflict erupted when he sought support with King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

Carol I and then, as the National Liberals deeply resented Romania's alliance with the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

, he approached the Germans for backing. Eliza Brătianu''Averescu - 1918''

at th

''Memoria'' Virtual Library

retrieved October 16, 2007 Subsequently, he was commander of the First Infantry Division (stationed in

Turnu Severin

Drobeta-Turnu Severin (), colloquially Severin, is a city in Mehedinți County, Oltenia, Romania, on the northern bank of the Danube, close to the Iron Gates. "Drobeta" is the name of the ancient Dacian and Roman towns at the site, and the modern ...

) and, later, of the Second Army Corps in Craiova. In 1912, he became a major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

, and, in 1911–1913, he was Chief of the General Staff The Chief of the General Staff (CGS) is a post in many armed forces (militaries), the head of the military staff.

List

* Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff ( United States)

* Chief of the General Staff (Abkhazia)

* Chief of General Staff (Af ...

. In the latter capacity, Averescu organized the actions of Romanian troops operating south of the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

in the Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies r ...

(the campaign against Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

, during which his troops met no resistance).

World War and first cabinet

During the World War (which Romania entered in 1916), General Alexandru Averescu led the Second Romanian Army in the successful defense of thePredeal Pass

Predeal Pass (, hu, Tömösi-szoros) is a mountain pass (elevation ) in the Carpathian Mountains in Romania. It connects the Prahova River valley to the south with the lowlands around Brașov to the north. It separates the Southern Carpathians (Bu ...

, and was then moved to the head of the Third Army (following the latter's defeat in the Battle of Turtucaia

The Battle of Turtucaia ( ro, Bătălia de la Turtucaia; bg, Битка при Тутракан, ''Bitka pri Tutrakan''), also known as Tutrakan Epopee ( bg, Тутраканска епопея, ''Tutrakanska epopeya'') in Bulgaria, was the openi ...

). He commanded Army Group South in the Flămânda operation against the Third Bulgarian Army and other forces of the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

, ultimately stopped by the German offensive (Averescu's forces did not register important losses, and orderly retreated to Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

, where Romanian authorities had taken refuge from the successful German operations).

Averescu again led the Second Army to victory in the

Averescu again led the Second Army to victory in the Battle of Mărăști

The Battle of Mărăști ( ro, Bătălia de la Mărăști) was one of the main battles to take place on Romanian soil in World War I. It was fought between 22 July and 1 August 1917, and was an offensive operation of the Romanian and Russian arm ...

(August 1917); his achievements, including his brief breakthrough at Mărăști, were considered impressive by public opinion and his officers. However, several military historians rate Averescu and his fellow Romanian generals very poorly, arguing that, overall, their direction of the war "could not have been worse". Despite controlling an army of 500,000 plus 100,000 Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

reinforcements, they were defeated by a German-Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen, see Austrian nationality law

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example: ...

-Bulgarian army of 910,000 in less than four months of combat.

Averescu was widely seen as the person behind a relatively successful resistance to further offensives on Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

(the single piece of territory still held by the Romanian state), and he was considered by many of his contemporaries to have stood in contrast to what was seen as endemic corruption and incompetence.Lucian Boia

Lucian Boia (born 1 February 1944 in Bucharest) is a Romanian historian. He is mostly known for his debunking of historical myths about Romania, for purging mainstream Romanian history from the deformations due to ideological propaganda. I.e. as ...

, ''History and Myth in Romanian Consciousness'', Central European University

Central European University (CEU) is a private research university accredited in Austria, Hungary, and the United States, with campuses in Vienna and Budapest. The university is known for its highly intensive programs in the social sciences and ...

Press, Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

, 2001 , p.210-211 The state of affairs, together with the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

in Russia, was to be blamed for the eventual Romanian surrender to the Central Powers; promoted Premier by King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

Ferdinand I during the period of crisis, Averescu began armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

talks with August von Mackensen

Anton Ludwig Friedrich August von Mackensen (born Mackensen; 6 December 1849 – 8 November 1945), ennobled as "von Mackensen" in 1899, was a German field marshal. He commanded successfully during World War I of 1914–1918 and became one of t ...

in Buftea and Focșani

Focșani (; yi, פֿאָקשאַן, Fokshan) is the capital city of Vrancea County in Romania on the banks the river Milcov, in the historical region of Moldavia. It has a population () of 79,315.

Geography

Focșani lies at the foot of the Curv ...

, but was vehemently opposed to the terms — he resigned, leaving the Alexandru Marghiloman

Alexandru Marghiloman (4 July 1854 – 10 May 1925) was a Romanian conservative statesman who served for a short time in 1918 (March–October) as Prime Minister of Romania, and had a decisive role during World War I.

Early career

Born in Buz ...

cabinet when it signed the Treaty of Bucharest.Ion Constantinescu, "«Domnilor, vă stricați sănătatea degeaba...»" ("«Gentlemen, You're Ruining Your Health over Nothing...»"), in ''Magazin Istoric'', July 1971, p.23, 26 Despite Averescu's talks yielding no result, he was repeatedly attacked by his political adversaries for having initiated them.

During the period, he also faced a Russian Bolshevik military action: just before Averescu came to power, as Russia's

During the period, he also faced a Russian Bolshevik military action: just before Averescu came to power, as Russia's Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

negotiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace, separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russian SFSR, Russia and the Central Powers (German Empire, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Kingdom of ...

with Germany, the ''Rumcherod

Rumcherod () was a self-proclaimed and short-lived organ of Soviet power in the South-Western part of Russian Empire that functioned during May 1917–May 1918. The name stands as the Russian language abbreviation for its full name Central Exe ...

'' administrative body in Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

, led by Christian Rakovsky

Christian Georgievich Rakovsky (russian: Христиа́н Гео́ргиевич Рако́вский; bg, Кръстьо Георги́ев Рако́вски; – September 11, 1941) was a Bulgarian-born socialist revolutionary, a Bolshevi ...

, ordered an offensive from the east into Romania. Stelian Tănase"Cristian Racovski" (Part I)

, in ''Magazin Istoric'', April 2004; retrieved October 16, 2007 In order to prevent further losses, Averescu signed his name to a much-criticized temporary armistice with the ''Rumcherod''; eventually, Rakovsky was himself faced with a German offensive (sparked by the temporary breakdown of negotiations at Brest-Litovsk), and had to abandon both his command and the base in Odessa.

People's Party

Character

Averescu quit the army in the spring of 1918, aiming for a career in politics — initially, with a message that was hostile to the National Liberal Party (PNL) and its leaderIon I. C. Brătianu

Ion Ionel Constantin Brătianu (, also known as Ionel Brătianu; 20 August 1864 – 24 November 1927) was a Romanian politician, leader of the National Liberal Party (PNL), Prime Minister of Romania for five terms, and Foreign Minister on se ...

.

He presided over the People's Party (initially named ''People's League''), and he was immensely popular especially among peasants after the end of the war. His force had an appealing populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

message, translated into vague promises and relying on the image of the General: peasants had been promised land at the beginning of the war (and they were being rewarded with it at the very moment, through an agrarian reform Agrarian reform can refer either, narrowly, to government-initiated or government-backed redistribution of agricultural land (see land reform) or, broadly, to an overall redirection of the agrarian system of the country, which often includes land re ...

that reached its full scope in 1923); they had formed the larger part of the Army, and had come to see Averescu as the one to fulfill their expectations, as well as a figure who was still commanding their allegiance. Eliza Brătianu, the PNL leader's wife, placed Averescu's ascension in the context of Greater Romania

The term Greater Romania ( ro, România Mare) usually refers to the borders of the Kingdom of Romania in the interwar period, achieved after the Great Union. It also refers to a pan-nationalist idea.

As a concept, its main goal is the creation ...

's creation through the addition of Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Be ...

, Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter BergerT ...

, and Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

(while making use of the condescending National Liberal tone towards the Romanian National Party

The Romanian National Party ( ro, Partidul Național Român, PNR), initially known as the Romanian National Party in Transylvania and Banat (), was a political party which was initially designed to offer ethnic representation to Romanians in the ...

that was emerging triumphant in previously Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

Transylvania):

" heso very harsh losses uring the war the defeats suffered by theAs the movement initially tended to describe itself as a social trend rather than aOld Kingdom In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth ..., the traces of foreign domination in the newly acquired provinces, but most of all the state of unhealthy euphoria that had taken hold of Transylvania, who had begun, in all good faith, to believe that only she had made the union happen, all of these have created a sort of insecurity within the borders of reater Romania"

political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific political ideology ...

, it also attracted former members of the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

(such as Constantin Argetoianu

Constantin Argetoianu ( – 6 February 1955) was a Romanian politician, one of the best-known personalities of interwar Greater Romania, who served as the Prime Minister between 28 September and 23 November 1939. His memoirs, ''Memorii. Pentr ...

, Constantin Garoflid

Constantin is an Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian and Romanian male given name. It can also be a surname.

For a list of notable people called Constantin, see Constantine (name).

See also

* Constantine (name)

* Konstantin

The first name Konsta ...

, and Take Ionescu), military men such as Constantin Coandă

Constantin Coandă (4 March 1857 – 30 September 1932) was a Romanian soldier and politician.

Biography

Constantin Coandă was born in Craiova. He reached the rank of general in the Romanian Army, and later became a mathematics profes ...

, the Democratic Nationalist Party leader A. C. Cuza

Alexandru C. Cuza (8 November 1857 – 3 November 1947), also known as A. C. Cuza, was a Romanian far-right politician and economist.

Early life

Born in Iași, Cuza attended secondary school in his native city and in Dresden, Saxony, Germany, ...

, the notorious supporters of ''dirigisme

Dirigisme or dirigism () is an economic doctrine in which the state plays a strong directive (policies) role contrary to a merely regulatory interventionist role over a market economy. As an economic doctrine, dirigisme is the opposite of ''lai ...

'' Mihail Manoilescu

Mihail Manoilescu (; December 9, 1891 – December 30, 1950) was a Romanian journalist, engineer, economist, politician and memoirist, who served as Foreign Minister of Romania during the summer of 1940. An active promoter of and contributor to f ...

and Ştefan Zeletin,Z. Ornea

Zigu Ornea (; born Zigu Orenstein Andrei Vasilescu"La ceas aniversar – Cornel Popa la 75 de ani: 'Am refuzat numeroase demnități pentru a rămâne credincios logicii și filosofiei analitice.' ", in Revista de Filosofie Analitică', Vol. II, N ...

, ''Anii treizeci. Extrema dreaptă românească'' ("The 1930s: The Romanian Far Right"), Editura Fundației Culturale Române, Bucharest, 1995, p.48, 243 the moderate nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

Duiliu Zamfirescu

Duiliu Zamfirescu (30 October 1858 – 3 June 1922) was a Romanian novelist, poet, short story writer, lawyer, nationalist politician, journalist, diplomat and memoirist. In 1909, he was elected a member of the Romanian Academy, and, for a while ...

, the future diplomat Citta Davila, the journalist D. R. Ioaniţescu, the left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

agrarianist Petru Groza

Petru Groza (7 December 1884 – 7 January 1958) was an Austro-Hungarian-born Romanian politician, best known as the first Prime Minister of the Communist Party-dominated government under Soviet occupation during the early stages of the Commu ...

, the Bukovinian leader Iancu Flondor

Iancu Flondor (3 August 1865 – 19 October 1924) was a Romanian politician who advocated Bukovina's union with the Kingdom of Romania.

He was born in the town of Storozhynets ( ro, Storojineṭ) in Northern Bukovina (now in Ukraine). His paren ...

, and the lawyer Petre Papacostea. Additional support came from Transylvanian activists such as Octavian Goga

Octavian Goga (; 1 April 1881 – 7 May 1938) was a Romanian politician, poet, playwright, journalist, and translator.

Life and politics

Goga was born in Rășinari, near Sibiu.

Goga was an active member in the Romanian nationalisti ...

and Teodor Mihali, who had previously left the Romanian National Party

The Romanian National Party ( ro, Partidul Național Român, PNR), initially known as the Romanian National Party in Transylvania and Banat (), was a political party which was initially designed to offer ethnic representation to Romanians in the ...

there in protest over the policies of its president Iuliu Maniu

Iuliu Maniu (; 8 January 1873 – 5 February 1953) was an Austro-Hungarian-born lawyer and Romanian politician. He was a leader of the National Party of Transylvania and Banat before and after World War I, playing an important role in the U ...

. Nevertheless, the People's Party did attempt to approach Maniu for an alliance at various intervals after summer 1919 (according to Argetoianu, their attempts were frustrated by King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

Ferdinand I, whose relationship with Maniu was cordial at the time, and who allegedly stated "Maniu is no one else's! Maniu is mine!").

The grouping also established close links with ''Garda Conștiinței Naționale'' (GCN, "The National Awareness Guard"), a reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the ''status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abse ...

group formed by the electrician Constantin Pancu

Constantin is an Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian and Romanian male given name. It can also be a surname.

For a list of notable people called Constantin, see Constantine (name).

See also

* Constantine (name)

* Konstantin

The first name Konstant ...

, engaged in violence against communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

activists in Iași

Iași ( , , ; also known by other alternative names), also referred to mostly historically as Jassy ( , ), is the second largest city in Romania and the seat of Iași County. Located in the historical region of Moldavia, it has traditionally ...

(the latter were feared by Averescu as well).Francisco Veiga, ''Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919-1941: Mistica ultranaționalismului'' ("History of the Iron Guard, 1919-1941: The Mystique of Ultra-Nationalism"), Bucharest, Humanitas

''Humanitas'' is a Latin noun meaning human nature, civilization, and kindness. It has uses in the Enlightenment, which are discussed below.

Classical origins of term

The Latin word ''humanitas'' corresponded to the Greek concepts of '' philanthr ...

, 1993 (Romanian-language version of the 1989 Spanish edition ''La mística del ultranacionalismo (Historia de la Guardia de Hierro) Rumania, 1919–1941'', Bellaterra, Publicacions de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

The Autonomous University of Barcelona ( ca, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona; , es, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona; UAB), is a public university mostly located in Cerdanyola del Vallès, near the city of Barcelona in Catalonia, Spain.

...

, ), p.46-47, 86, 89, 91-93, 98, 252-253, 247-248 Nevertheless, in late 1919, Averescu and Argetoianu approached the Socialist Party of Romania

The Socialist Party of Romania ( ro, Partidul Socialist din România, commonly known as ''Partidul Socialist'', PS) was a Romanian socialist political party, created on December 11, 1918 by members of the Social Democratic Party of Romania (PSDR) ...

and its associate, the Social Democratic Party of Transylvania and Banat, with an offer for collaboration, negotiating the matter with the parties' reformist

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can eve ...

leaders — Ioan Flueraş

Ioan is a variation on the name John found in Romanian, Bulgarian, Russian, Welsh (), and Sardinian. It is usually masculine. The female equivalent in Romanian and Bulgarian is Ioana. In Russia, the name Ioann is usually reserved for the cle ...

, Ilie Moscovici

Ilie B. Moscovici (also known as Tovilie; 28 November 1885 – 1 November 1943) was a Romanian socialist militant and journalist, one of the noted leaders of the Romanian Social Democratic Party (PSDR). A socialist since early youth and a party ...

, and Iosif Jumanca

Iosif Jumanca (December 23, 1893 – June 26, 1950) was an Austro-Hungarian and Romanian politician.

Born in Fólya, Temes County (now Folea, Timiș County) in 1903 he became a founding member of the Romanian branch of the Hungarian Social Dem ...

. At the time, Argetoianu claimed, his conversations with Moscovici revealed the fact that the latter was growing suspicious of the party's far left wing, where "the blanket-maker Cristescu and others were agitating". Averescu proposed merging the two parties, as a distinct section, into the People's Party; he was refused, and talks broke down when the general expected the Socialists to support his electoral platform.

Impact

According to Eliza Brătianu (who was comparing Averescu with the French rebel soldierGeorges Boulanger

Georges Ernest Jean-Marie Boulanger (29 April 1837 – 30 September 1891), nicknamed Général Revanche ("General Revenge"), was a French general and politician. An enormously popular public figure during the second decade of the Third Repub ...

), several voices inside his movement called on Averescu to lead a republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

''coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

'' against King Ferdinand and her husband — a move allegedly prevented only by the general's loyalism

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British C ...

. Argetoianu, who admitted that "I shook hands with Averescu ..expecting a dictatorial regime", claimed that, during his stay in Italy, the general had been decisively influenced by Radicalism and the ''Risorgimento

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

'' movement. This, in Argetoianu's view, was the cause for his repeated involvement in conspiracies

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, is a secret plan or agreement between persons (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder or treason, especially with political motivation, while keeping their agree ...

; he recalled that, in 1919, Davila's house was the scene of regular reunion of officers, who plotted Brătianu's ousting and pondered dethroning the king (in this version of events, Averescu initially accepted to be proclaimed dictator, but, around October of that year, called on conspirators to renounce their plan).

Aiming to answer most of Romania's social and political issues, the League's founding document called for:

"A land reform, with the passage of the land which is at the momentAccording to Argetoianu,expropriated Eminent domain (United States, Philippines), land acquisition (India, Malaysia, Singapore), compulsory purchase/acquisition (Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, United Kingdom), resumption (Hong Kong, Uganda), resumption/compulsory acquisition (Austr ...only on principle - a reference to the 1917 promise for a land reforminto the effective and immediate ownership of villagers through the means ofcommunes An intentional community is a voluntary residential community which is designed to have a high degree of social cohesion and teamwork from the start. The members of an intentional community typically hold a common social, political, relig ...; anelectoral reform Electoral reform is a change in electoral systems which alters how public desires are expressed in election results. That can include reforms of: * Voting systems, such as proportional representation, a two-round system (runoff voting), instant-ru ..., throughuniversal suffrage Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stanc ...,direct election Direct election is a system of choosing political officeholders in which the voters directly cast ballots for the persons or political party that they desire to see elected. The method by which the winner or winners of a direct election are cho ...,secret ballot The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot, is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vote ..., andcompulsory voting Compulsory voting, also called mandatory voting, is the requirement in some countries that eligible citizens register and vote in elections. Penalties might be imposed on those who fail to do so without a valid reason. According to the CIA World F ..., with representation given toethnic minorities The term 'minority group' has different usages depending on the context. According to its common usage, a minority group can simply be understood in terms of demographic sizes within a population: i.e. a group in society with the least number o ..., since the latter would not hinder the free manifestation of political individualities; administrative decentralization."

"in the autumn of 1919, verescu'spopularity had reached its peak. In the villages, people would dream of him, some swore that they had seen him descending from an airplane into their midst, others, who had fought in the war, told that they had lived by his side in theAlthough he was alsotrenches A trench is a type of excavation or in the ground that is generally deeper than it is wide (as opposed to a wider gully, or ditch), and narrow compared with its length (as opposed to a simple hole or pit). In geology, trenches result from erosi ..., it was through him that hopes were solidified, and he was expected of to provide a miracle for people to live a carefree and fulfilling life. His popularity was somethingmystical Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ..., something supernatural, and all sorts of legends had begun to surround thisMessiah In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; , ; , ; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...of the Romanian people." Ioan Scurtu

"Mit și realitate. Alexandru Averescu" ("Myth and Reality. Alexandru Averescu")

, in ''Magazin Istoric'', May 1997; retrieved October 16, 2007

Prime Minister of Romania

The prime minister of Romania ( ro, Prim-ministrul României), officially the prime minister of the Government of Romania ( ro, Prim-ministrul Guvernului României, link=no), is the head of the Government of Romania. Initially, the office was s ...

for three mandates (1918, 1920–1921, 1926–1927), his political success is not as spectacular as the military one. Averescu ended up as one of the pawns maneuvered by Brătianu. Argetoianu later repeatedly expressed his distaste for Averescu's hesitant stance and openness to compromise.

Second cabinet

Establishment

Initially, Brătianu approached Averescu using their shared displeasure over theAlexandru Vaida-Voevod

Alexandru Vaida-Voevod or Vaida-Voievod (27 February 1872 – 19 March 1950) was an Austro-Hungarian-born Romanian politician who was a supporter and promoter of the Union of Transylvania with Romania, union of Transylvania (before 1920 part of ...

Romanian National Party

The Romanian National Party ( ro, Partidul Național Român, PNR), initially known as the Romanian National Party in Transylvania and Banat (), was a political party which was initially designed to offer ethnic representation to Romanians in the ...

(PNR)- Peasants' Party (PȚ) cabinet; the National Liberals managed to obtain the general's renunciation of his goal to prosecute their party for alleged mis-management of Romania before and during the war, as well as his promise to respect the 1866 Constitution of Romania when carrying out the planned land reform. At the same time, Brătianu kept a tight relationship with King Ferdinand.

On March 13, 1920, he gave news of the Vaida-Voevod cabinet's dissolution, and was widely expected to call for early elections as soon as this had happened. Instead, he read a document convened with King Ferdinand, which suspended Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

(the first legislative body in ''Greater Romania

The term Greater Romania ( ro, România Mare) usually refers to the borders of the Kingdom of Romania in the interwar period, achieved after the Great Union. It also refers to a pan-nationalist idea.

As a concept, its main goal is the creation ...

'') for ten days — the measure was intended to give Averescu the time to negotiate a new majority in the chambers. Ioan Scurtu"Prăbuşirea unui mit" ("A Myth's Crumbling")

, in ''Magazin Istoric'', March 2000; retrieved October 16, 2007 These moves caused a vocal response from the opposition:

Nicolae Iorga

Nicolae Iorga (; sometimes Neculai Iorga, Nicolas Jorga, Nicolai Jorga or Nicola Jorga, born Nicu N. Iorga;Iova, p. xxvii. 17 January 1871 – 27 November 1940) was a Romanian historian, politician, literary critic, memoirist, Albanologist, poet ...

, who was president of the Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourbon R ...

and sided with the National Party, called for a motion of no confidence

A motion of no confidence, also variously called a vote of no confidence, no-confidence motion, motion of confidence, or vote of confidence, is a statement or vote about whether a person in a position of responsibility like in government or mana ...

to be passed on March 26; in return, Averescu obtained the support of the monarch in dissolving the Parliament, and invested his cabinet's energies into winning the early elections by enlisting the help of county

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

-level officials (local administration came to be dominated by People's Party officials).Ion Constantinescu, "Dr. N. Lupu: «Dacă și d-ta ai fi fost bătut...»" ("Dr. N. Lupu: «If You Yourself Had Been Beaten...»"), in ''Magazin Istoric'', August 1971, p.37-41 It carried the vote with 206 seats (223 together with Take Ionescu's Conservative-Democratic Party

The Conservative-Democratic Party (, PCD) was a political party in Romania. Over the years, it had the following names: the Democratic Party, the Nationalist Conservative Party, or the Unionist Conservative Party.

The Conservative-Democratic Part ...

).

As agreements between the PNR and PȚ broke down (with the PNR awaiting for new developments), the PȚ joined Iorga's party, the Democratic Nationalists, in creating the ''Federation of National-Social Democracy'' (which also drew support from the group around Nicolae L. Lupu

Nicolae L. Lupu (November 4, 1876 – December 4, 1946) was a Romanian left-wing politician and social physician. Originally a leader of the Labor Party, which was joined with the Peasants' Party, Lupu served as Interior Minister in 1919–19 ...

).

Policies

His mandate was marked by the signing of theTreaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (french: Traité de Trianon, hu, Trianoni békeszerződés, it, Trattato del Trianon) was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in ...

with Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, and initial steps leading to the creation of the Little Entente

The Little Entente was an alliance formed in 1920 and 1921 by Czechoslovakia, Romania and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (since 1929 Yugoslavia) with the purpose of common defense against Hungarian revanchism and the prospect of a Ha ...

—formed by Romania with Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

. It was also at this stage that Romania and the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of ...

inaugurated their military alliance (''see Polish–Romanian alliance

The Polish–Romanian alliance was a series of treaties signed in the interwar period by the Second Polish Republic and the Kingdom of Romania. The first of them was signed in 1921 and, together, the treaties formed a basis for good foreign rela ...

''). The goal to create a ''cordon sanitaire

''Cordon sanitaire'' () is French for "sanitary cordon". It may refer to:

*Cordon sanitaire (medicine), a cordon that quarantines an area during an infectious disease outbreak

*Cordon sanitaire (politics), refusal to cooperate with certain politic ...

'' against Bolshevist Russia also brought him and his Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

Argetoianu to oversee repression measures against the group of Socialist Party of Romania

The Socialist Party of Romania ( ro, Partidul Socialist din România, commonly known as ''Partidul Socialist'', PS) was a Romanian socialist political party, created on December 11, 1918 by members of the Social Democratic Party of Romania (PSDR) ...

members who voted in favor of joining the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

(arrested on suspicion of "attempt against the state's security" on May 12, 1921).Cristina Diac"La «kilometrul 0» al comunismului românesc. «S-a terminat definitiv cu comunismul in România!»" ("At «Kilometer 0» in Romanian Communism. «Communism in Romania Is Definitely Over!»")

, in ''

Jurnalul Național

''Jurnalul Național'' is a Romanian newspaper, part of the INTACT Media Group led by Dan Voiculescu, which also includes the popular television station Antena 1. The newspaper was launched in 1993. Its headquarters is in Bucharest

Buchare ...

'', October 6, 2004; retrieved October 16, 2007Cristian Troncotă, "Siguranța și spectrul revoluției comuniste" ("Siguranța

Siguranța was the generic name for the successive secret police services in the Kingdom of Romania. The official title of the organization changed throughout its history, with names including Directorate of the Police and General Safety ( ro, Di ...

and the Specter of Communist Revolution"), in ''Dosarele Istoriei'', 4(44)/2000, p.18-19 This came after a long debate in Parliament over the imprisonment of Mihai Gheorghiu Bujor, a Romanian citizen who had joined the Russian Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

in Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Be ...

during the later stages of the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

, and who had been tried for treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

. Argetoianu, who proclaimed communism to be "over in Romania", later indicated that Averescu and other members of the cabinet were hesitant about the crackdown, and that he ultimately resorted to taking initiative for the arrests — thus presenting his fellow politicians with a '' fait accompli''.

The regions coming under Romania's administration at the end of the war still maintained their ad hoc

Ad hoc is a Latin phrase meaning literally 'to this'. In English, it typically signifies a solution for a specific purpose, problem, or task rather than a generalized solution adaptable to collateral instances. (Compare with ''a priori''.)

Com ...

administrative structures, including the Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

n Directory Council, set up and dominated by the PNR; Averescu ordered these dissolved in April, facing protest from local notabilities.Irina Livezeanu

Irina Livezeanu (born 1952) is a Romanian-American historian. Her research interests include Eastern Europe, Eastern European Jewry, the Holocaust in Eastern Europe, and modern nationalism. Several of her publications deal with the history of Roma ...

, ''Cultural Politics in Greater Romania: Regionalism, Nation Building and Ethnic Struggle, 1918–1930'', Cornell University Press

The Cornell University Press is the university press of Cornell University; currently housed in Sage House, the former residence of Henry William Sage. It was first established in 1869, making it the first university publishing enterprise in th ...

, New York City, 1995 , p.23-24 At the same time, he ordered all troops to be demobilized

Demobilization or demobilisation (see spelling differences) is the process of standing down a nation's armed forces from combat-ready status. This may be as a result of victory in war, or because a crisis has been peacefully resolved and milita ...

. He unified currency around the Romanian leu

The Romanian leu (, plural lei ; ISO code: RON; numeric code: 946) is the currency of Romania. It is subdivided into 100 (, singular: ), a word that means "money" in Romanian.

Etymology

The name of the currency means "lion", and is derive ...

, and imposed a land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultura ...

in the form in which it was to be carried out by the new Brătianu executive. In fact, the latter measure had been imposed by the outgoing PNL cabinet through the order of Ion G. Duca

Ion Gheorghe Duca (; 20 December 1879 – 29 December 1933) was Romanian politician and the Prime Minister of Romania from 14 November to 29 December 1933, when he was assassinated for his efforts to suppress the fascist Iron Guard movement.

...

, in a manner which Argetoianu described as "destructive". As an initial step, Averescu's government appointed the noted activist Vasile Kogălniceanu, a deputy for Ilfov County

Ilfov () is the county that surrounds Bucharest, the capital of Romania. It used to be largely rural, but, after the fall of Communism, many of the county's villages and communes developed into high-income commuter towns, which act like suburbs ...

, as ''rapporteur

A rapporteur is a person who is appointed by an organization to report on the proceedings of its meetings. The term is a French-derived word.

For example, Dick Marty was appointed ''rapporteur'' by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Eur ...

''; Kogălniceanu used this position to give an account of the agrarian situation in Romania, stressing the role played by his ancestor, Constantin

Constantin is an Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian and Romanian male given name. It can also be a surname.

For a list of notable people called Constantin, see Constantine (name).

See also

* Constantine (name)

* Konstantin

The first name Konsta ...

, in abolishing Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

n serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

, as well as that of his father, Mihail Kogălniceanu

Mihail Kogălniceanu (; also known as Mihail Cogâlniceanu, Michel de Kogalnitchan; September 6, 1817 – July 1, 1891) was a Romanian liberal statesman, lawyer, historian and publicist; he became Prime Minister of Romania on October 11, 1863 ...

, in eliminating ''corvée

Corvée () is a form of unpaid, forced labour, that is intermittent in nature lasting for limited periods of time: typically for only a certain number of days' work each year.

Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state for the purposes of ...

s'' throughout Romania.

The People's Party found itself hard pressed to limit the effects of the reform as promised by Duca — reason why Constantin Garoflid

Constantin is an Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian and Romanian male given name. It can also be a surname.

For a list of notable people called Constantin, see Constantine (name).

See also

* Constantine (name)

* Konstantin

The first name Konsta ...

, seen by Argetoianu as "the Conservative and theorist of large-scale landed property

In real estate, a landed property or landed estate is a property that generates income for the owner (typically a member of the gentry) without the owner having to do the actual work of the estate.

In medieval Western Europe, there were two compet ...

", was promoted as Minister of Agriculture. Argetoianu also accused the Premier of endorsing reform in an even more radical shape, and contended that:

" ..peasants blessed «father Averescu», who gave them land, and rallied around him even tighter. Brătianu, Duca, they were nowhere mentioned except in curses. O, human gratitude!"In October 1920, Averescu reached an agreement with the Allied Powers, recognizing Bessarabia's union with Romania — expressing a hope for the Bolshevik government to be overthrown, it also imposed the region's cession on a projected democratic government in Russia (while calling for further negotiations between it and Romania); throughout the

interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

refused to bind itself to the provisions of the agreement. Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

also refused to ratify the document, citing, alongside various foreign interests (including its friendship with the Soviet Union),Charles Upson Clark

Charles Upson Clark (1875–1960) was a professor of history at Columbia University. He discovered the Barberini Codex, the earliest Aztec writings on herbal medicines extant.

Biography

Clark was born in 1875 to Edward Perkins Clark and Cat ...

''Bessarabia. Russia and Roumania on the Black Sea'': Chapter XXVIII, "The Tatar-Bunar Episode"

at the

University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW, simply Washington, or informally U-Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington.

Founded in 1861, Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast; it was established in Seattle a ...

; retrieved October 16, 2007Dumitru Hîncu, "O acțiune politică contestată. Descoperiri în arhivele Ministerului de externe din Viena" ("A Controversial Political Action. Discoveries in the Vienna Foreign Ministry Archives"), in ''Magazin Istoric'', November 1995, pp. 68–70 the 250 million Italian lire

The lira (; plural lire) was the currency of Italy between 1861 and 2002. It was first introduced by the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy in 1807 at par with the French franc, and was subsequently adopted by the different states that would eventually f ...

owed to Italian investors in Romanian state bonds.

Scandals and fall

In March 1921, Argetoianu became implicated in a scandal involving the actions of his associate Aron Schuller, who had attempted to contract a 20 million lire loan with a bank in Italy, using ascollateral

Collateral may refer to:

Business and finance

* Collateral (finance), a borrower's pledge of specific property to a lender, to secure repayment of a loan

* Marketing collateral, in marketing and sales

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Collate ...

Romanian war bond

War bonds (sometimes referred to as Victory bonds, particularly in propaganda) are debt securities issued by a government to finance military operations and other expenditure in times of war without raising taxes to an unpopular level. They are ...

s that he had illegally obtained from the Finance Ministry reserve.

With Nicolae Titulescu

Nicolae Titulescu (; 4 March 1882 – 17 March 1941) was a Romanian diplomat, at various times government minister, finance and foreign minister, and for two terms president of the General Assembly of the League of Nations (1930–32).

Early ye ...

as Finance Minister, Averescu resumed the interventionist course in economic policies, but broke with tradition when he attempted to legislate a major increase in taxes and proposed nationalization

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

s — with potential negative effects on the PNL-voting middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Commo ...

.Joseph Slabey Rouček, ''Contemporary Roumania and Her Problems'', Ayer Publishing, Manchester, New Hampshire

Manchester is a city in Hillsborough County, New Hampshire, United States. It is the most populous city in New Hampshire. At the 2020 census, the city had a population of 115,644.

Manchester is, along with Nashua, one of two seats of New Hamp ...

, 1971, p.106, 111-113 The National Liberals, through the voice of Alexandru Constantinescu-Porcu, helped exploit the rivalry between the Peasants' Party and Iorga, using the latter's rejection of Constantin Stere

Constantin G. Stere or Constantin Sterea (Romanian; russian: Константин Егорович Стере, ''Konstantin Yegorovich Stere'' or Константин Георгиевич Стере, ''Konstantin Georgiyevich Stere''; also known u ...

(a conflict sparked by Stere's support for Germany during the World War); Stere won partial elections for the deputy seat in Soroca

Soroca (russian: link=no, Сороки, Soroki, uk, Сороки, Soroky, pl, Soroki, yi, סאָראָקע ''Soroke'') is a city and municipality in Moldova, situated on the Dniester River about north of Chișinău. It is the administrative ...

, Bessarabia, causing a political scandal which saw all parties (including the PNR) declare their dissatisfaction. The conflict worsened during a prolonged parliamentary debate over Averescu's proposal to nationalize enterprises in Reșița

Reșița (; german: link=no, Reschitz; hu, Resicabánya; hr, Ričica; cz, Rešice; sr, Решица/Rešica; tr, Reşçe) is a city in western Romania and the capital of Caraș-Severin County. It is located in the Banat region. The city had ...

(an initiative the opposition mistrusted, alleging that the new owners were to be People's Party members), when Argetoianu addressed a mumbled insult to the Peasant Party's Virgil Madgearu

Virgil Traian N. Madgearu (; December 14, 1887 – November 27, 1940) was a Romanian economist, sociologist, and left-wing politician, prominent member and main theorist of the Peasants' Party and of its successor, the National Peasants' Part ...

. Ion G. Duca

Ion Gheorghe Duca (; 20 December 1879 – 29 December 1933) was Romanian politician and the Prime Minister of Romania from 14 November to 29 December 1933, when he was assassinated for his efforts to suppress the fascist Iron Guard movement.

...

of the PNL expressed his sympathies to Madgearu (who had repeated out an obscene word whispered by Argetoianu), and all opposition groups appealed to Ferdinand, asking for Averescu's recall (July 14, 1921).

Ferdinand then attempted to facilitate a fusion between the Romanian National Party

The Romanian National Party ( ro, Partidul Național Român, PNR), initially known as the Romanian National Party in Transylvania and Banat (), was a political party which was initially designed to offer ethnic representation to Romanians in the ...

and the National Liberals, but negotiations broke down after disagreements over the possible leadership. Eventually, Brătianu convened with Ferdinand his return to power, and the king called on Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

Take Ionescu to resign, thus causing a political crisis that profited the PNL and put an end to the Averescu cabinet.

Shows of popular support in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

were called of by Averescu himself, after he had negotiated with Brătianu for a People's Party cabinet to be formed "at a proper time". Ionescu took over as premier until late January 1922, when he was replaced by Brătianu.

Third cabinet

New political alliances

In early 1926, the general was again named Premier, and approached the PNR and its close ally, the Peasants' Party, proposing a merger around his leadership. This met with a stiff refusal, as it seemed that the two were about to win the elections with additional support, but the king, suspicious of theleft-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

credentials of the Peasants' Party, used his Royal Prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in th ...

and nominated Averescu as premier (with PNL support).Ion Constantinescu, "V. Madgearu: «Rechinii așteaptă prada!»" (" V. Madgearu: «The Sharks Await Their Pray!»"), in ''Magazin Istoric'', October 1971, p.81-82

Averescu's party was instead joined by PNR dissidents, Vasile Goldiș

Vasile Goldiș (12 November 1862 – 10 February 1934) was a Romanian politician, social theorist, and member of the Romanian Academy.

Early life

He was born on 12 November 1862 in his grandfather's (Teodor Goldiș) house in the village of M ...

and Ioan Lupaș

Ioan Lupaș (9 August 1880 – 3 July 1967) was a Romanian historian, academic, politician, Orthodox theologian and priest. He was a member of the Romanian Academy.

Biography

Lupaș was born in Szelistye, now Săliște, Sibiu County (at the time ...

, who represented a Romanian Orthodox

The Romanian Orthodox Church (ROC; ro, Biserica Ortodoxă Română, ), or Patriarchate of Romania, is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church in full communion with other Eastern Orthodox Christian churches, and one of the nine patriarchates ...

segment of the Transylvanian voters (rather than the Greek Catholics The term Greek Catholic Church can refer to a number of Eastern Catholic Churches following the Byzantine (Greek) liturgy, considered collectively or individually.